As the coronavirus pandemic threatened to overwhelm Chinese hospitals last year, Chinese resellers appear to have colluded to inflate the prices of ventilators and other essential medical equipment from multinational companies including Siemens, GE, and Philips, according to a review of public records on the sale of medical equipment in China.

The inflated prices did not translate into oversized profits for the multinationals. Rather, they appear to be part of a complex system through which third-party resellers allegedly camouflaged bribes to corrupt hospital officials. Court cases and further interviews suggest that regional representatives of the multinationals themselves at times tolerated or were directly involved in bribery schemes.

(PART 1 OF A TWO-PART SERIES)

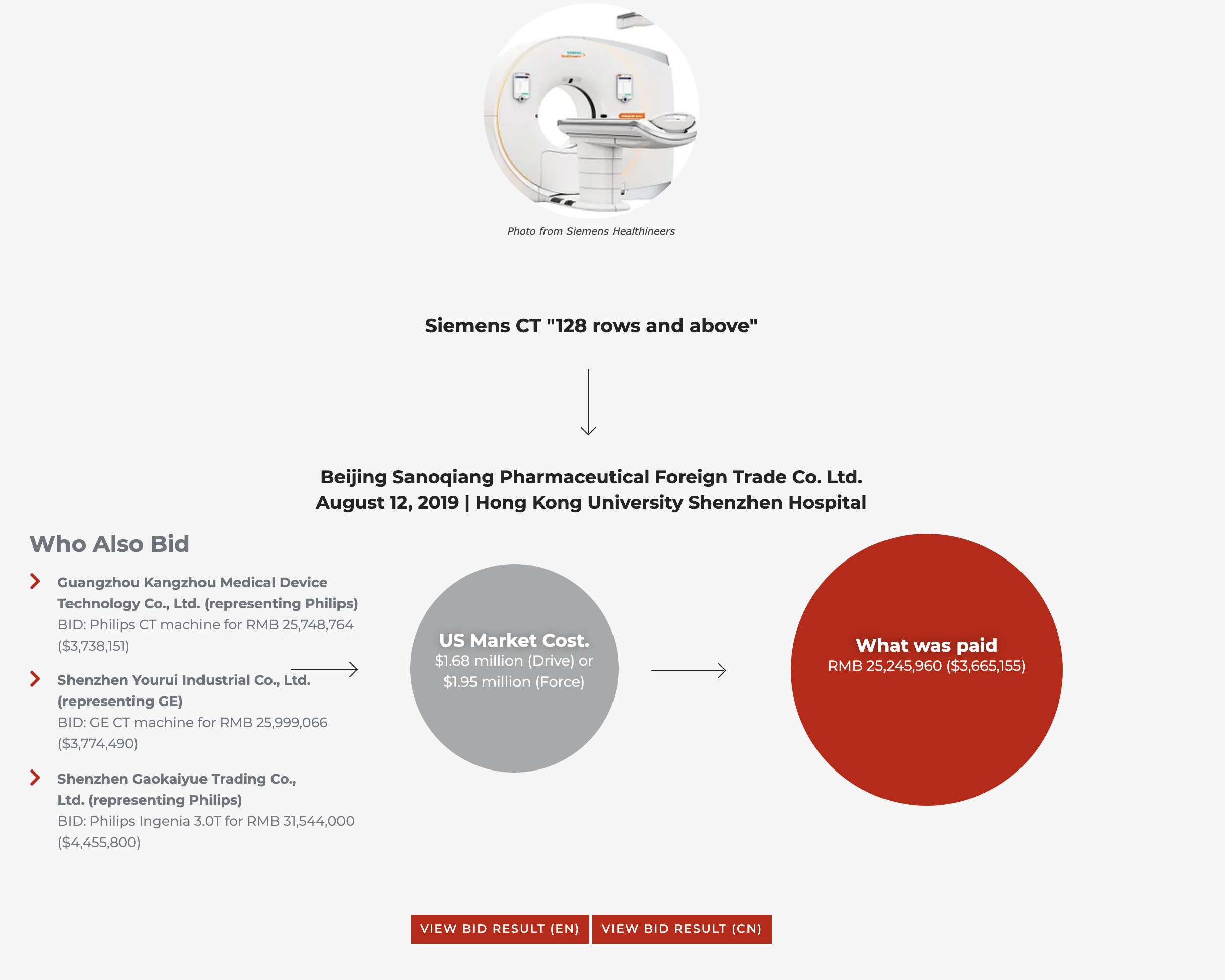

High-value MRIs, CT scanners, ultrasound machines and other equipment – all vital for diagnosing and researching the novel coronavirus – were sold for prices that ran from thousands to millions of dollars above their U.S. market prices. A Siemens CT scanner sold for $3.24 million at one hospital in China, when the top-of-the-line Siemens model carries a market price of $1.95 million. A GE Signa Pioneer MRI scanner sold to one Chinese hospital through a reseller for $5.1 million, while another hospital paid half that, $2.56 million, for the same machine.

A new search of public databases of purchases by Chinese hospitals, as well as recent court verdicts, reveals that despite pledges of reform, bad practices that led to criminal investigations and bribery convictions for the multinationals in the past have persisted with very little interference from corporate compliance departments – and were not slowed by the coronavirus outbreak.

Instead, the data suggests Chinese resellers representing major Western firms routinely submit coordinated, inflated bids to hospitals. The testimonies contained in past court cases, meanwhile, lay out how resellers agree on prices in advance in order to have a margin to pay bribes.

The bidding documents, which usually include the price to the end user, often contain such detailed technical specifications that it would be difficult for anyone other than employees of the manufacturers themselves to draw them up, suggesting that firms like Siemens, GE and Philips are at best tacitly assisting resellers engaged in bribery.

For Siemens in particular this represents a relapse into tolerating corruption, since the company was the subject of an unprecedented global bribery scandal in 2008, which led to one of the biggest corporate fines in history at $1.6 billion, followed by pledges of reform.

The new revelations suggest a “familiar cycle,” according to former corporate investigator Peter Humphrey, who worked in China for several years investigating corporate corruption, at one point bringing a case to court against pharmaceutical giant GlaxoSmithKline. In the aftermath of the case, Humphrey, a former Reuters correspondent, served two years in a Chinese prison for buying personal data.

“In my experience, companies neglect due diligence, turn a blind eye to corruption, until the bomb goes off,” Humphrey said. “Then the bomb goes off, they’re in trouble, part of the response is to launch a stronger compliance function, but after a number of years they revert to form.”

“The jungle grows back,” he said.

The costs of corruption have only climbed during the pandemic, as have their consequences, according to a recent Transparency International report. Unless “robustly countered,” the organization predicted, “pervasive cross-border corruption in health care will cost additional lives.”

Dangerous Resellers

Public tenders from across China are collected on the website chinabidding.com, a search of which reveals numerous suspicious deals. For instance, in May 2020 the Fifth People’s Hospital of Jingzhou, in the Hubei province not far from Wuhan, paid ¥2.4 million, or $340,000, for a GE Logiq S8 ultrasound.

The base price for a GE Logiq S8 ultrasound machine in the US is around $70,000, though additional features could raise the price to $150,000. Even the most high-end ultrasound machines don’t sell for more than $250,000 on the US market, according to the non-profit organization ECRI, which offers independent advice about medical devices for professionals in the US.

GE would not comment specifically on this deal or any of the others in this article, but in a statement, a GE spokesperson said, “We are committed to integrity, compliance and the rule of law in every country in which we do business.”

GE also insisted that the third-party resellers involved in such deals were not company representatives or agents, but GE’s customers. As such, the company maintains not only that it had no control over the prices resellers charged hospitals for its products, but that for GE to even know the price for the end-user would violate antitrust law in both the US and China, as this would be considered Resale Price Maintenance (RPM).

Antitrust lawyers dispute GE’s interpretation, noting that the laws don’t prevent a manufacturer from simply knowing the price that a reseller sets. Nor do they bar manufacturers’ employees from providing support to resellers submitting public tenders of their equipment. Indeed, China’s Ministry of Commerce requires declarations from manufacturers confirming that resellers in fact act as agents, rather than merely customers, of the manufacturers.

In another bid, from November 2019, a Chinese reseller sold Newport ventilators made by the US-Irish company Medtronic for ¥295,000, or $42,000, to the Southern Medical University Hospital of Integrated Traditional Chinese and Western Medicine.

The same machine, known as a Covidien e360 ventilator, sells for less than half that price on medical tech retail websites in the United States. In a statement, Medtronic said it did not control distribution pricing, and that many factors can influence how a product is priced. “Reseller pricing can further vary in China based on the nature of services associated with product delivery, education and training, and product service and support, among other factors,” a Medtronic spokesman said in an emailed statement.

But insiders in the Chinese health care market say none of those factors explain the price disparities. “If you look at the bidding documentation and the global prices, you can still see a huge gap in between,” said Meng-Lin Liu, a former Siemens compliance officer in China, who has analyzed dozens of such transactions. Hospitals pay the high bidding price to the resellers, but the resellers only pay the normal global price to the multinationals, Liu alleges. “Then afterwards they distribute this slush money to the relevant party, mostly the hospital decision-makers.”

Liu alleged exactly these kinds of bribery schemes in Siemens China ten years ago, before the company fired him. He brought a whistleblower retaliation lawsuit against the company in New York in 2014. (The facts of the case were never litigated. The court rejected the case partly on the grounds that the relevant law does not apply to a foreign national working for a foreign company. A Siemens spokesman said in a statement that Liu left the company by “mutual termination agreement,” while Klaus Moosmayer, Siemens’ Chief Compliance Officer at the time, said Liu was terminated following “performance issues.”)

Subsidiaries of the State

Many of the GE and Siemens sales cited in this article went through subsidiaries of Sinopharm, the short name of the China National Pharmaceutical Group Corporation (CNPGC), a huge state-owned conglomerate with $70 billion in revenue last year. Where manufacturers bypassed intermediaries to sell directly to hospitals, prices were often competitive with the US and European markets – scuppering arguments that tariffs or other legitimate charges unique to the Chinese market are behind the higher cost of equipment.

Bribing foreign public officials, such as hospital officials in a public health care system, is illegal under the US Foreign Corrupt Practices Act (FCPA). Hence the need for middlemen, who offer a form of legal insulation. In a country like China, where economic power flows from the political elite, FCPA experts say multinationals do their best to avoid scrutinizing how sales are made, or collude with corruption while maintaining a veneer of compliance. But as Tom Fox, veteran FCPA lawyer and independent consultant, put it, “Under the FCPA, it’s of zero consequence who sells the equipment; the manufacturer is liable. It doesn’t matter what you call it: Whether it’s a reseller, whether it’s a distributor or an agent – if I’m selling Siemens equipment, Siemens is 100 percent always liable for the bribery.”

Matt Kelly, publisher of the Radical Compliance newsletter, noted that the SEC has prosecuted several US companies for corruption in China. In some cases, sales executives in China had their employees keep separate spreadsheets and use private email systems to work on certain deals. Price discrepancies, where the difference between the reseller’s price and the real sales price is used as a bribe, are not uncommon.

“There is a lot that local executives at any large company would be able to try to do to keep head offices from knowing, and they would certainly find willing co-conspirators in intermediaries and hospital officials and regulators in China, who would be receiving the bribes,” Kelly said.

In 2018, Germany’s Süddeutsche Zeitung reported on the involvement of employees of Western companies in bribery in Chinese health care, as did The New York Times a year later, based on bribery trials in Chinese courts. This all came a decade after Siemens agreed to pay one of the biggest fines in corporate history in 2008 as part of a plea agreement with the SEC over accusations of a global bribery network.

“Obviously the consequence of this bribery is that China’s health sector is overpaying for certain goods and services such as MRI scanners,” said Humphrey.