A copper rush sparks last-ditch battles for Arizona’s soul

Silver Bell Mine, just northwest of Tucson, Arizona, is shielded from the suburban homes nearby behind rocky hills and barbed wire. Seen from above, it is an upside-down Machu Picchu: vast open pits terraced deep into the earth, some with bright-turquoise, toxic pools at the bottom. House-size trucks haul copper ore under a ghostly haze of dust. Rock, 1.8 million tons a month, piles high along the perimeter. At 19,000 acres, the mine site is larger than Manhattan.

Top: Cottonwood tree in Las Cienegas National Conservation Area, near the proposed Rosemont site.

The view is mesmerizing, almost beautiful in a way, until its significance sinks in. This hellscape was once rich, saguaro-studded Sonoran desert, and Silver Bell—which is now fighting to take 11,000 adjacent acres from the Ironwood Forest National Monument—is just one part of a bigger picture. It’s also, very likely, a preview of worse to come.

Copper has been central to Arizona’s psyche since territorial days. Today, with a copper-star flag flying at the copper-domed capitol in Phoenix, the state still accounts for a huge amount of America’s production—68 percent—and the industry is growing. But with only about 0.3 percent of the workforce employed in copper mining, it is not the economic powerhouse it once was. The state’s real asset is the natural grandeur that draws visitors from across the continent and the oceans. The compact Santa Rita mountain range alone, between Tucson and the Mexican border, offers one of the country’s richest patches of biodiversity: wetlands, grasslands, desert, and thorny scrub, rising through thick forests to high cliffs and sheltering threatened species from orchids to jaguars.

But now a new Arizona copper rush, in the Santa Ritas and beyond, is menacing that natural wealth and sparking the passions of a nineteenth-century range war. Global companies are moving fast, spurred by various challenges to mining abroad and shifting regulatory priorities in Washington, as well as by the bright future of their product. (Copper is indispensable to almost anything electric or electronic.) Working mines like Silver Bell are increasing capacity. And two new projects, both massive and foreign-owned, are pushing ahead as once staunch opposition from regulators drops away.

Top: An aerial view of the Silver Bell Mine, operated by the Mexican-owned mining company Asarco, in southern Arizona. The company is now fighting to take 11,000 adjacent acres from the Ironwood Forest National Monument. Support for aerial photographs provided by LightHawk, based in Fort Collins, Colorado.

“This goes way beyond one beautiful valley,” Randy Serraglio, an ecologist fighting one of the mines and the Southwest conservation advocate at the Center for Biological Diversity, in Tucson, told me in June. Modern copper mines devastate landscapes, typically depleting huge amounts of water and covering vast areas with piles of toxic mine waste, and virtually always discharging harmful pollutants. But at a moment when a twenty-one-year drought is expected to get worse and the population, up fivefold since the 1960s, is still growing fast, the stakes are higher than they’ve ever been. “This is a profound conflict over what is happening to the American West,” Serraglio said.

The immediate danger is from Rosemont Mine, about thirty miles southeast of Tucson in the heart of the Santa Ritas. After more than a decade of conflict with regulatory agencies, conservationists, and Native American tribes, the project is nearing final approval.

In June of last year, the US Forest Service gave its blessing for Hudbay Minerals of Toronto to dig a pit, projected to be a mile in diameter and half a mile deep, on 4,200 acres of mostly public land. The only significant barrier left is the need for a Clean Water Act permit from the US Army Corps of Engineers. (The Corps’ regional office recommended against issuing one, but the application has since moved up the chain of command.) Meanwhile, in a Rosemont feasibility study issued last year, Hudbay told investors about additional mineral resources outside the boundary of the planned pit with “potential for economic extraction.” (Rosemont’s projected working life span is nineteen years, but it could be much longer; copper mines often keep going as additional reserves are confirmed and exploited. Hudbay said that it has no plans to mine these additional resources in the foreseeable future, and that such action would require additional permits.)

Back in 2012, things looked bleaker for Rosemont. The US Bureau of Land Management’s Tucson office, which oversees a nearby watershed, issued a chilling assessment of the company’s plan, writing, “What is certain is that the pit would cause a profound lowering of the regional aquifer.” A steep new underground gradient would be created, pulling groundwater from every direction, and Rosemont would be constantly pumping water out of the pit. Even after the mine closed, water would keep flowing into the pit and evaporating under the Arizona sun. The impacts to groundwater, the BLM assessment continued, “are likely to cause the slow but eventual collapse of the aquatic ecosystem,” a kind of collapse that is “irreversible, cannot be mitigated and will last for centuries.”

Top: Part of the active Silver Bell Mine.

In the Santa Ritas, the impact would be devastating in other ways. Serraglio notes that the mine site is located at an important juncture of a habitat critical to the recovery of jaguars in the United States, where a male thrived for three years until 2015. No jaguar is likely to make a home there with thousands of acres fenced off and streams running dry. The surrounding area also includes rare desert riparian zones, waterside habitats running along two creeks that are home to threatened Chiricahua leopard frogs, endangered Gila topminnows, and extremely rare Coleman’s coralroot orchids.

For the Tohono O’odham tribe, whose traditional lands include the mine site, the issues go far beyond ecology. “The destruction is forever,” Edward Manuel, the tribal chairman, told me. “Our wealth is the land. If we lose what is sacred to us, what is left for our children?”

Near the edge of the tribe’s reservation, west of the Rosemont site, Baboquivari Peak looms above the desert. It is where the tribe believes I’itoi, the Man in the Maze, emerged to populate the universe, and they revere all within view of the summit, which includes the Santa Ritas. Women gather cactus fiber there for watertight baskets iconic of the tribe; men trek there for spiritual guidance and to hunt. A lawsuit filed against the Forest Service in April by the Tohono O’odham and two other tribes identifies more than a hundred burial sites and hallowed spots, some dating back a thousand years, that would be damaged or obliterated by the mine, or placed off limits. Tribal roots in the Santa Ritas, the suit says, are 10,000 years deep. (Hudbay would not comment on ongoing litigation, but said that an archaeologist and a tribal representative would monitor mine activity for any disturbance to human remains and artifacts.)

The Environmental Protection Agency, which last year issued an analysis emphasizing its longstanding and serious doubts about the project and the scientific claims behind it, could still veto a Clean Water Act permit. But that’s very much in question, given the agency’s current leadership. Either way, there is sure to be more litigation.

The tribes’ suit has now been combined with two others brought by conservation groups into litigation challenging both the Forest Service and the US Fish and Wildlife Service over their approvals of the Rosemont plan. Oral arguments are expected to begin late this year.

But Julia Fonseca, Pima County’s point person on mining and the environment, worries it may not be enough. “If Rosemont is approved, and there is no court injunction while lawsuits drag on,” she said, the company “can destroy the area as fast as they can, and then just tell everyone, ‘It’s all over, go home and settle down.’”

Top: The global price of copper, posted daily at the entrance to Freeport-McMoRan’s Sierrita Mine.

Two hours north, in Pinal County, in the traditional copper belt east of Phoenix, the Resolution mine threatens another riparian area and public land sacred to the Apache. Owned by London-based Rio Tinto and the Australian conglomerate BHP, Resolution would dig down 7,000 feet from an area near the edge of Apache Leap, a bluff where legend holds that Apache warriors jumped to their deaths rather than be captured by the approaching US Cavalry. It would also burrow under Oak Flat, a 760-acre area of great cultural and religious significance to the Apache, with petroglyphs and other evidence of native presence dating back centuries. An 839-acre parcel that includes Apache Leap has been set aside for protection, but some environmental scientists believe that mine activity could still do serious damage to the cliff face. It would definitely decimate Oak Flat, creating what the company has called a “cave zone” about a mile long, which after forty years could sink up to a thousand feet. Because the company would continuously pump groundwater out of the mine, there’s a strong risk that water levels will be reduced for miles around, with potentially devastating consequences for the life in and around a nearby creek. (Rio Tinto said its computer modeling shows that although the cave zone will expand over time, it will still be fifteen hundred feet from Apache Leap in fifty years. Both the company and a spokesperson for the Tonto National Forest, where Oak Flat and Apache Leap are located, said impacts to the cliff and to local water supplies are being analyzed as part of the regulatory review process. BHP did not respond to requests for comment.)

Top: Jose Federico Lopez, seventy-five, lives on a ridge overlooking Asarco’s copper smelter in Hayden, where he drove heavy equipment around the slag heap for many years. In 2011, the Environmental Protection Agency found that Asarco’s smelter had been continuously emitting illegal amounts of dangerous air pollutants, including arsenic and lead, and the company is now required to spend $150 million to install new technology to reduce emissions.

In 1955, Dwight Eisenhower signed an executive order protecting Oak Flat from copper mining. But in 2005, Jeff Flake, then an Arizona congressman with ties to mining—he had previously lobbied for a Rio Tinto mine in Namibia— joined Arizona colleagues in putting forward a land-swap bill: 2,400 acres of land owned by the Forest Service, including Oak Flat, would go to Resolution in exchange for land elsewhere in the state. Later, Flake and John McCain pressed for the swap in the Senate, and despite the Obama Administration’s resistance, it was added as a rider to the National Defense Authorization Act for 2015. Pending final approval from various agencies under the National Environmental Policy Act, the land will become Resolution’s private property.

Below: A sample of chrysocolla, a copper ore mineral, at the University of Arizona Gem and Mineral Museum.

In 2014, a group calling itself Apache Stronghold was formed to resist the project. It holds regular ceremonies to consolidate opposition and focus attention on the imminent threat. In February, the group organized a fifty-mile march to Oak Flat across mountainous terrain, beginning east of the mine site, on the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation. The march passed through the mining towns of Miami and Globe, ending in the green expanse of oak and manzanita known as Chi’Chil’Ba’Goteel to the Apache. Dozens made the journey and were met by hundreds more at Oak Flat.

That evening, the group joined in centuries-old rites, with masked dancers embodying the living spirits of the surrounding mountains. The next morning, Wendsler Nosie Sr., the former tribal chairman at San Carlos and an Apache Stronghold leader, guided the group in a prayer ceremony at a hilltop shrine known as Holy Ground—four upright crosses with eagle feathers installed permanently at the campground. One by one, participants passed through the poles in silent prayer. Nosie, in a black T-shirt and jeans, with sunglasses perched on his battered hat, showed flashes of humor.

But mostly he was solemn. This was not political, he said; it was a religious re-awakening, an effort to return to and protect the original sacred places.

Nosie warned that pro-mining forces would thwart them any way they could. Two weeks later, mysterious vandals chopped down the four poles of the Holy Ground at Oak Flat and trampled the feathers into the dirt. (Resolution condemned the vandalism and said it respects the tribe’s “right to engage in peaceful protest.”)

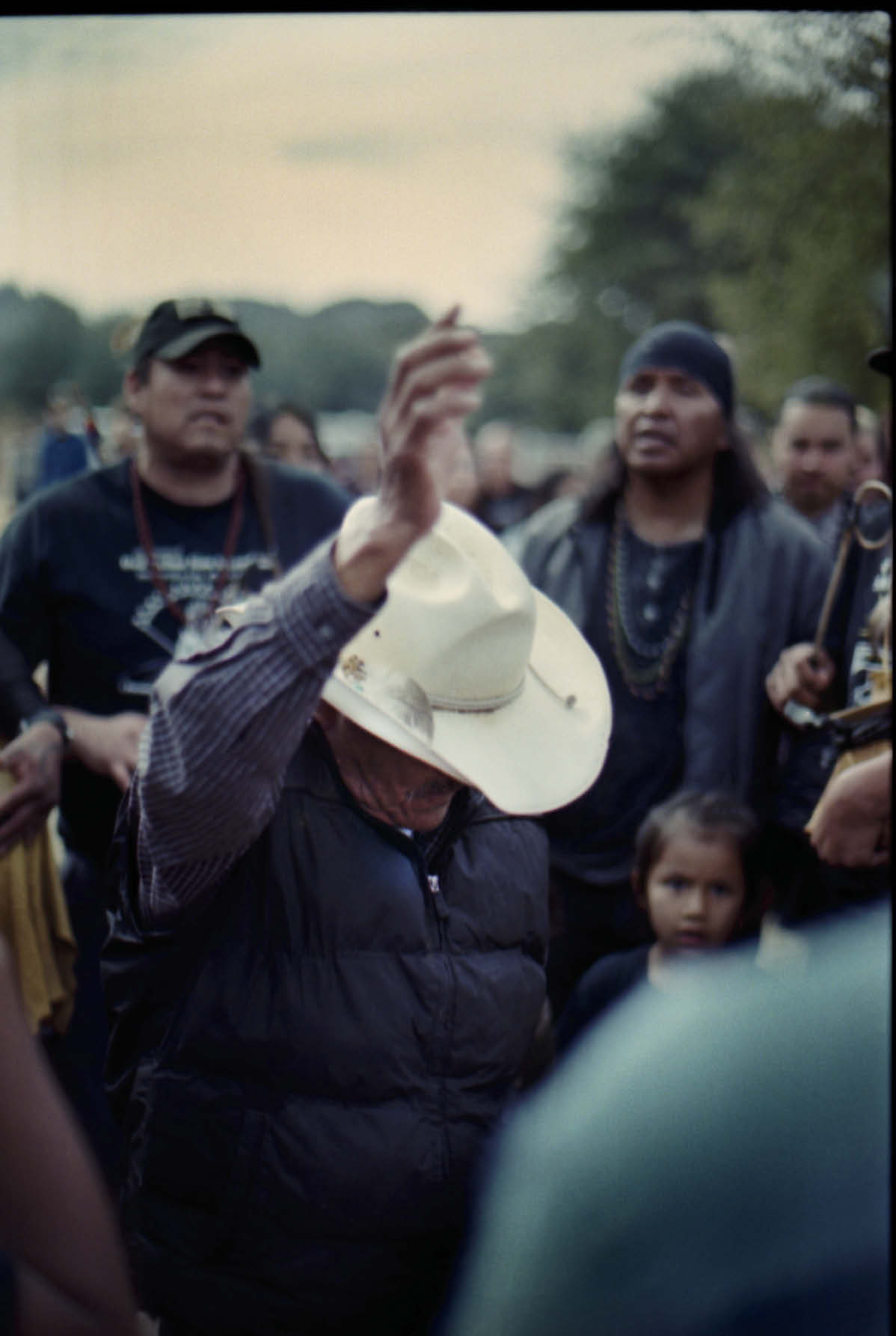

Top: Anthony Logan, an Apache singer and medicine man, leads a prayer at Oak Flat in February. Wendsler Nosie Sr. (pictured in the background to the right), a former chairman for the San Carlos Apache Tribe, has led ongoing efforts to protect Oak Flat, an area the tribe considers sacred, from destruction by the Resolution mine.

The companies behind Rosemont and Resolution, as companies tend to do, say they will pump money into the economy. But despite their insistence that they aim to hire locally as much as possible, it’s likely that after initial construction, many jobs at both mines would go to skilled staff and managers cycled in from elsewhere. Both plan to ship copper concentrate to Asia for smelting, with profits going to Canada, Britain, and Australia. And all copper mining companies both foreign and domestic take advantage of an 1872 law meant to develop the West, which gives them rights to exploit public land for only token payment.

Meanwhile, the areas around the mines would sacrifice money-generating potential, and even after the mines closed, permanent scars would cripple tourism and recreation. It’s not hard to find evidence of that kind of damage around Arizona. Silver Bell is the smallest of three mines in the state owned by Asarco. A 119-year-old company started by East Coast tycoons, it is now part of Grupo México, which is notorious for union- busting and a calamitous toxic spill in the state of Sonora. Its chairman is Germán Larrea Mota-Velasco; Forbes estimates his mining, railroads, and publishing wealth at $15 billion.

Top: A rainstorm over Oak Flat, the proposed site of the Resolution mine. The Apache hold this land and its surrounding mountains sacred, in large part because of the abundance of water. Resolution’s block-cave mining technique would cause much of the landscape to cave in. Left: Petroglyphs at Oak Flat. Below: Cottonwoods grow along a creek in Gaan Canyon, renamed Devil’s Canyon, an important riparian corridor near the proposed site of the Resolution mine.

Besides Silver Bell and Mission Mine near Tucson, Asarco operates the Ray mine in Pinal County, which in past decades has swallowed three towns. The company resettled the living and moved the exhumed dead to a desolate cemetery down the road. It also owns a smelter nearby at Hayden, which is surrounded by slag heaps and waste mountains. Once lively and thriving, Hayden is now a virtual ghost town, nearly empty of businesses, as well as a Superfund site that Asarco is attempting to clean up after the EPA found it to be a major source of hazardous air pollutants, including arsenic and lead. (The company did not respond to requests for comment.)

Foreign owners aren’t the only ones responsible: Arizona’s biggest working mine, Morenci, is American-owned. East of Phoenix near the New Mexico border, Morenci Mine is a series of linked craters that straddle the Coronado Trail Scenic Byway for eight miles and are visible from space. The highway winds upward through moonscape until it finally gives way to tall pines, oaks, and lush undergrowth. Here, too, the land is public, but the obsolete 1872 law, which few politicians seem interested in changing, holds sway. Arizona requires a severance tax, but it is just 1.25 percent of a company’s net revenue. With costs low, operations can go on indefinitely, chewing up splendor for increasingly lower-grade ore.

Morenci now belongs to Freeport- McMoRan, which in 2007 acquired the mine’s owner, Phelps Dodge, a controversial colossus that has been cited as potentially responsible for multiple Superfund sites. Its Sierrita Mine, near Tucson, is still bedeviled by an inherited sulfate plume, and has had to install several wells to keep sulfates from entering local drinking water.

Below: Nizhoni Pike, seventeen, at a spring near Oak Flat that was the site of her Sunrise Ceremony, an important Apache coming-of-age tradition. Pike, like her grandfather Wendsler Nosie Sr., has worked with the activist group Apache Stronghold to resist the Resolution project and call attention to the sacred nature of the land the mine could disturb. Since the turn of the nineteenth century, the Apache, confined to prison camps and later reservations, were largely denied access to land and water formerly used for religious rites. Pike’s ceremony at Oak Flat was part of an Apache effort to return to original holy places to properly perform such rites.

At Sierrita, executives exiting the main gate pass an electronic display of orange numbers every night: the usually climbing prices of copper and of the company’s stock, FCX, which rose 34 percent in 2017.

Old hands have a rule of thumb about mining: distant ownership tends to disregard local communities. The defunct Magma Copper Company, known as Mother Magma because it looked after workers and spent heavily on public works, was sold in 1995 to the Australian company that is now BHP, Rio Tinto’s partner at Resolution. In the 1950s, the developer Del Webb had built a model company town, San Manuel, near what was then the world’s largest underground copper mine. In 2002, BHP shut down the operations, citing “international copper reserve management strategy.” That is, prices, and profits, declined.

More than 2,200 people lost their jobs, and San Manuel began to empty out. Soon after, BHP’s small maintenance staff left. With no pumping in abandoned shafts, the pit flooded, so that Arizona now loses yet more scarce water to the sun, and underground mining—the less destructive kind—is now impossible.

BHP’s original name was Broken Hill Proprietary, and at San Manuel, broken hills are what it left behind. Only a few businesses hang on in what is now a bedroom community for Tucson and mines to the north. A high fence seals off a vast expanse of hiking and biking country: flooded galleries and pits are a potential nightmare for liability lawyers.

Inside the perimeter, heavy equipment rusts away. Placards scream keep out, warning that violators will be prosecuted to the full extent of state statutes. An overseas company left that mess. Now it threatens trespassers under Arizona law.

Top: A saguaro cactus grows in the collapsed and unstable ground of the abandoned San Manuel Copper Mine. BHP, the Australian company that bought the mine from the defunct Magma Copper Company, shut down the project in 2002.

Photographs by Samuel James, text by Mort Rosenblum. Samuel James is a photographer based in North Carolina. Mort Rosenblum is a reporter based in Arizona and France. The text of this story was supported by the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the City University of New York Graduate School of Journalism. Ana Arana contributed to it.